Relationship Between the political Literacy of Youth and Economic Development in

Sri Lanka: A Historical Overview since 2000-2020

January 05, 2023

By Pansilu A. Pussedeniya

Author Biography

Author Biography

Pansilu Aloka Puassadeniya is a third year undergraduate of General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University and currently following the Degree in Strategic studies and International Relations. Currently she iis completing her intership in Institute of National Security Studies as a research intern. She went to Yasodara Devi Balika Vidyalaya Gampaha and she was the former Deputy Head Prefect of the school(2018). She was the assistant vice president education in KDU Toastmasters club. She also participated for a gender equality leadership programme organized by the East West Center in Hawaii. She has presented a research at the International Research Conference held in 2020 and 2021. Her interest is to study more on history of the society and its relationship with other disciplines.

Abstract

The study of youth, political literacy, and civic activity is a complicated endeavor that is normatively laden, according to the authors of this brief historical review of the study of the political socialization process and the acquisition of political knowledge. In addition to design rigor, the research calls for a deeper knowledge of the agents, activities, and relationships that influence young people's perceptions of the political environment and their decision to engage or not. In Sri Lanka, youth are crucial to the country's political and economic progress. Each nation's social, political, and historical settings and developments determine this function. One such crucial element that defines and affects the kind and extent of political participation by young, which by default stays mainly passive, is the elders' supremacy in Sri Lanka's traditional communities. Unlike in developing nations, young political activity in developed and industrially advanced nations does not play a significant role since the institutions have already matured, are firmly established, and are accepted by society. However, the nature and extent of youth-led political participation in emerging nations, where political and economic institutions are changing, continues to be important. The role of youth is vital in developing nations whose political and economic institutions are changing because they confront unique social, economic, and political difficulties. This is in contrast to the nature and breadth of young-led political action in developed countries. The study's primary goal is to investigate the kind and extent of young political involvement in Sri Lanka.

Key Words : Political Literacy, Youth, Economic Development

Chapter 1

Introduction

The term "youth" is not universal and has different meanings in different societies and nations. While lawmakers define youth based on age, psychologists describe youth as "the interval between puberty and maturity." "Youth is a stage in the life of the individual during which she/he develops her/his vocational skills," according to economic theory. When social status is taken into account, youth may be described as an investment era (Sessional Paper III, 1967). While the Sri Lanka National Youth Service Council (NYSC) defines youth as "persons within the age category of 13-29" (Ibargüen, 2004), the United Nations defines youth as "persons those within the age bracket of 15 to 24 years." Other than the age restriction, nations like Sri Lanka define youth using certain socio-cultural factors like marriage and work. Youth were defined as those between the ages of 15 and 29 who were not married in Sri Lanka's National Youth Survey (NYS), which was performed in 2000. This study uses a definition of youth that includes both men and women between the ages of 15 and 29 who are married or single. In terms of education, it's a never-ending process of giving life purpose. We have been informed about environmental changes for ages through mechanisms that are available in the sociopolitical structure. The transmission of cultural legacy from one generation to the next is made possible through the acquisition of knowledge, skills, values, morals, beliefs, habits, and personal growth. For the purpose of resolving educational-related disputes, some Governments have granted the United Nations

Economic and Social Council (UNESCO) the public right to education. Education is delivered scientifically, which includes, in addition to regular instruction, training, storytelling, discussion, and guided study based on theories, philosophy, and empirical research, all while keeping socio-political growth in mind. The idea of compulsory education was introduced in the context of overall development, where children receive the necessary education during the time period mandated by the government in any registered school, and parents are encouraged to send their children on a regular basis where they are educated by effective teachers, free of charge with other amenities like a mid-day meal, free school uniforms, and school books. As a result, it is seen as a fundamental right in many nations. The government's mandatory education program offers mastery of both mental and physical abilities. In order to play a significant role in the development of the country, ethical values and social communication skills are also fostered. The idea of political maturity and each citizen's ability to make informed decisions to modernize the political system are closely related to social growth.

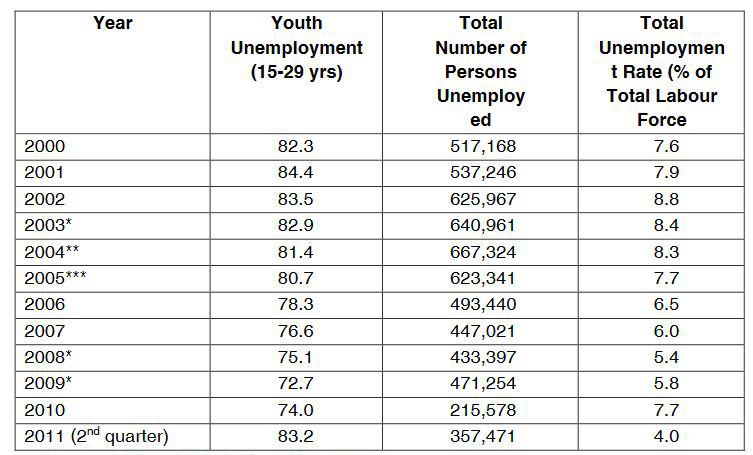

In Sri Lanka, the 15- to 29-year-old age group accounts for about 28 percent of the entire population. In addition, from 1960 to 2000, more than 75% of young people resided in rural areas (Ibargüen, 2004). The number of young people who do not attend school has significantly decreased, and throughout the years after independence, they have made good progress in their academic careers. In 2006/07, the literacy rate for youth (15–24 years) was 95.8%. In addition, in the elementary, intermediate, and tertiary grades, the proportion of females to boys was 99 percent, 105.7 percent, and 187 percent, respectively, in 2006/07. (Department of Census and Statistics, 2009). When compared to the national unemployment rate, the young unemployment rate was much higher. As can be seen in Table 1.1, the country's young unemployment rate ranged from 72.7 percent to 84.4 percent from 2000 to 2011. In Sri Lanka, the high prevalence of young unemployment is attributed to a number of issues. This involves waiting in line for a chance to get a "good job" in the public sector and having better education and skill mismatches (Ibargüen, 2004, Ministry of Labour Relations and Foreign Employment, 2006, Heltberg and Vodopivec, 2008).

Table 1.1: Youth Unemployment (Age Group of 15-29 Years)

Source: Damayanthi and Rambodagedara, 2013

Between 1991 and 2017, 65 percent of Sri Lanka's population between the ages of 15 and 59 were in the labor force, while the proportion of dependents under the age of 15 and those over 65 has declined in relation to the workforce. Such a population structure is advantageous for economic growth, thus the term "demographic dividend." This benefit was available to Sri Lanka till 2017. Demographers claim that in order to fully profit from such a dividend, there must be political stability, a youth-focused education system, concurrent social and economic progress, and kids who are prepared for the difficulties of a complex global economic system. The dividend has been used by nations like China, India, Vietnam, and Singapore to expand their economies and people resources. This component, together with certain historical elements related to Sri Lanka's post- colonialism, defines and influences young political participation. When the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna (M.E.P.) came to power in 1956, it was a significant turning point in Sri Lankan youth political action. The government's determination to expand university education, which had previously only been offered in English, the creation of two new institutions, and the lowering of the age requirement for universal suffrage from 21 to 18 all helped to increase young political engagement.

Methodology

This study used secondary data. Secondary data was mostly collected from Ministry of Youth Affairs and Skills Development and its’ affiliated institutions. In addition, secondary information was gathered through research reports, journals, newspaper articles and report of the Presidential Task Force on Youth Affairs etc.

Chapter 2

In nations with advanced technology, the process of changing from a traditional civilization to a contemporary one took several centuries. It was a gradual process that took some time to complete. Contrarily, emerging nations-especially Sri Lanka, which had spent centuries under the rule of three Western powers—undertook a variety of transformational transformations before and after gaining independence, and these adjustments sped up social and economic development in the years that followed. As a result, Sri Lanka is not just a developing nation but also a nation undergoing a rapid modernization process. This process of fast modernization within the framework of modest economic progress is blamed for many of the changes in the social, political, and cultural realms. The character of young people's social and political participation in Sri Lanka is ascribed to this modernization process, which began in the 1940s. The demographic makeup also played a role. The structure of the population was changed by social welfare practice and legislation, free health and social services implemented in the 1940s in particular, and an expanding young demographic. A country's development is sometimes attributed to its youthful population. However, political scientists claim that Sri Lanka's failure to use this demography as a catalyst for economic, social, and political growth has produced favorable conditions for corruption. Education is a related factor. The availability and access to free education from basic to university education increased as a result of the introduction of free education in 1945. New ideals and expectations were brought about by the widespread accessibility to free education, mass media, and urbanization. A concurrent political and economic development becomes necessary in this case for a smooth transition. This is especially pertinent to political stability since political stability is a prerequisite for economic progress. In the absence of concurrent economic growth and political stability, the youth would experience widespread discontent and be more likely to organize for violent political protest.

Social development denotes qualitative alterations to the framework and structure of society, and it ultimately achieves goals and objectives through upward-moving trends characterized by higher levels of vitality, effectiveness, caliber, productivity, complexity, creativity, mastery, enjoyment, and success. Global societies have had a significant development in all spheres of social development during the previous several centuries. We must educate ourselves about the most recent scientific theories and research if we are to advance. Social growth has been directed by advancements in science and education, which have enriched human resources and society's collective knowledge to meet difficulties. It is closely related to social and scientific concerns to maintain the development's ever-expanding process and achieve the exceptional social height in the global context. Youth are often given hope and anticipation via education, giving them the physical capacity and mental perspective to increase production and raise the general population's standard of life. Education plays a significant part in social development, which is a constant process based on better structures. It broadens the scope of social activity, improves the quality of the content, and attempts to include additional or excluded groups in the main social fabric.

Given that most democratic countries have multi-ethnic, multi-religious, and multi-caste societies, citizenship education is crucial and a fascinating topic of study. When there is no effective check on the political system's stated goals, the right to universal suffrage, which is granted to all people without distinction, is occasionally abused, the democratic spirit is weakened. Although there is a system in place to educate pupils about politics, socioeconomic considerations, living situations, and personality qualities have a detrimental impact on their willingness to engage in politics without regard for values. Since Plato and Aristotle established the tight connection between political education and the kind of government, the significance of political education has been a subject of debate. The democracies of today demand individuals who are capable of participating in democratic politics and who have the necessary knowledge, skills, and character. With significant democratization-related developments over the past three to four decades, the topic has drawn attention. Following this, nations started concentrating on pertinent studies, and it became clear that youth were becoming less interested due to their lack of understanding of politics and its significance in their lives.

The type of political action in Sri Lanka has been influenced by the increase of higher education options, particularly in the context of education. The foundation of higher education in Sri Lanka is credited to the founding of the University College in 1921 and later the University of Sri Lanka in 1942. The aristocratic models of Oxford and Cambridge in Britain served as the foundation for the early development of university education, which has now evolved into mainstream education. Although there are currently more than 40,000 students enrolled at the university each year, it is still unclear whether some of the degree programs in some faculties have been sufficiently revised and restructured to remain highly relevant and help graduates develop the skill set needed for the rapidly changing workforce. The public sector has been under pressure from successive administrations to hire graduates, but the nature of their deployment and use, the pay scale, and the career trajectories continue to be unsolved concerns. It should be stressed that in order to prevent education and employment from fueling violent youth activism, educational changes must go beyond these constraints. Political favoritism, excessive intervention in democratic processes, and inadequate administration, according to the Presidential Commission on Young Grievances established after the Second Uprising of the JVP in 1987-1989, are contributing reasons to youth rebellion.

The reaction of policy makers, particularly the government, determines the type and extent of young engagement, political process, and social and economic progress. One such program is the Youth Services Council, which was founded in 1969. While offering youth vocational training, welfare, recreation, and skill development, it aims to increase youth engagement and provide kids a voice. It is believed that the youth clubs set up at the lowest level of administrative entities serve as a vehicle for extensive youth engagement. The appointment of an ombudsman to handle youth complaints was suggested by the Presidential Commission on Youth Grievances. The panel put out suggestions to increase the number of young people serving in local government. When creating imperatives and policies to address youth challenges, further recommendations were made to set up channels for mass youth mobilization. However, it's crucial to remember that young engagement should follow the same rules and guidelines for fairness in representation as do youth representation. Demographers estimate that the proportion of workers between the ages of 15 and 59 in the workforce was 65 percent in 2006 and will decrease to 63.2 percent by 2031. The demographic dividend will therefore continue to be influential until 2070. Political stability is crucial for economic progress, thus development plans must recognize this, which necessitates radical reforms in K–12 and higher education institutions. Although Sri Lanka has developed sensible policies, their execution has been hampered by the absence of a bipartisan strategy and a commitment to radical change. One such politician who boldly pursued revolutionary change through the Paddy Lands Act, despite its personal ramifications to his political career, is the late Philip Gunawardena, who we honor today.

Chapter 3

But there are still innumerable cases in Sri Lanka when young people have been deprived of their rights and freedom. Numerous youth protests and rallies have been violently suppressed throughout the years, restricting their right to free speech. When police disrupt peaceful protests, they frequently turn violent and result in the reprimanding of adolescent campaigners. Youth in Sri Lanka are increasingly perceived as disruptors rather than agents of change, and officials and the media frequently mock them, destroying whatever authority or platform they may have had to voice their concerns and demand justice. Through our educational system, where pupils are instructed to listen, memorize, and regurgitate information, this silencing culture is normalized. Because of their rigid commitment to convention and tradition rather than reason or pragmatism, government initiatives to empower young frequently fail. In order to prioritize employment above liberty, youth empowerment programs appear to focus on theoretical knowledge devoid of critical thinking, producing social puppets that are simple targets for manipulation and mobilization for the benefit of others. We have fostered a culture in which young people are not taken seriously and are not seen as leadership potential. The government said that in 2015, 96 percent of Sri Lankans were literate. However, what proportion of this fraction is media literate? How many people are politically savvy? How many people are aware of their legal and basic rights? And even if they are aware, how many young people have the real authority to speak out for those? This is why youth empowerment initiatives need to be more concerned with freedom and rights than just jobs and the economy. We must provide our young the tools they need to appreciate and prioritize their own liberty while also promoting that of others in order to build a truly liberal and free society. To keep the democratic system running, this is necessary. The greatest pro-liberty network in the world, Students for Liberty (SFL), is made up of students, professionals, and concerned citizens from all over the world who collaborate to advance the freedom of everyone. The movement, which was started in 2008 by few students who were concerned about the widening gap between youth and liberty, quickly expanded into an international network of students and youth leaders who respect their freedom. SFL began its activities in Sri Lanka in 2019 with a group of dedicated young that support equal rights, freedom, and peace. SFL has been working in the regions of North America, the EU, Brazil, Africa, and South Asia for more than ten years. Since then, the Sri Lankan chapter of SFL has expanded, and it is now widely acknowledged as the only youth organization that primarily promotes the freedom and liberty of Sri Lanka's youth through awareness-raising, digital advocacy, training, research, and intervention, collaborating with local groups that operate at the grass-roots and policy levels like The Advocata Institute, Verite Research, and Hashtag Generation.

Chapter 4

Due to long lines for "better jobs" and a disconnect between the school system and the labor market, there is a high rate of voluntary work among young people in Sri Lanka. In order to shift youth and society's perspectives on the aforementioned concerns, relevant government and private sector organizations, particularly those connected to the education system, media, and young, should launch awareness campaigns. Taking manual, technical, and entrepreneurial employment as an example, government may run ads addressing work ethics, views, attitudes, and goals. Another tactic to lower young unemployment and meet the demand for labor from outside is the dissemination of information about work prospects and skill development. The greatest way to spread information about current career possibilities both domestically and abroad is through networking systems. Previous studies have shown that youth have extremely little faith in the bureaucracy, the police, and some political organizations (such as the federal government, province councils, local government institutions, and political parties). Furthermore, the politicization of society in Sri Lanka is a major contributor to young discontent and a host of other social issues, according to several study results and commission reports. The government needs to take steps to boost public confidence in its institutions and should pay close attention to the issue. Therefore, the greatest solution to the issue would be the introduction of a merit-based system and at least enough governance practices throughout all spheres of government. The Presidential Commission on Young made significant proposals in 1989 to improve youth engagement in politics and decision-making as well as to address social inequities and inequalities. Since the majority of the recommendations are still relevant in the current environment, the government and other interested parties, including political parties and labor unions, should take the necessary steps to put them into practice in order to increase youth participation in political, decision-making, social, and economic activities. The government may pass laws and regulations establishing minimum quotas for young people in civil society organizations, save for geriatric societies, representation in political institutions, and decision-making levels within political parties.

References

Damayanthi, M.K.N. and Rambodagedara, R.M.M.H.K., 2013, Factors Affecting Less Youth Participation in Smallholder Agriculture in Sri Lanka, Colombo: Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training Institute.

Damayanthi, M.K.N., 2005, The Role of Physical Capital in Alleviation of Poverty: Case Studies of Two Villages, Dissertation submission to University of Colombo for Postgraduate Diploma in Economic Development.

Government of Ceylon, 1967, Youth in Ceylon part I&II, Sessional Paper III, February 1967, Colombo: The Government Press.

Gunathilaka R., Markus Mayer, Vodopivec M., 2010, The Challengers of youth Employment in Sri Lanka. World Bank.

Heltberg, R. and Vodopivec, M., 2008, Sri Lanka: Unemployment, Job Security and Labour Market Reform, The Peradeniya Journal of Economics. 2(1&2) available at http://www.arts.pdn.ac.lk/econ/ejournal/v2/C_Heltberg-article.pdf. [accessed 13 October 2012].

Hettige S.T and Markus Mayer, M., 2002, Sri Lankan Youth Challenges and Responses, Sri Lanka: University of Colombo.

Hettige S.T Unrest or Revolt,(1996), Some Aspects of Youth Unrest in Sri Lanka, Geothe- Institute, American Studies Association , Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Kottegoda, S. 2004, Negotiating Household Politics. Women’s Strategies in Urban Sri Lanka. Colombo: Social Scientists Association.

Ministry of Finance and Planning, 2010, Sri Lanka the Emerging wonder of Asia: Mahinda Chinthana, Vision for the future, Colombo: Ministry of Finance and Planning National Youth Service Council, 1985, Needs of youth in Sri Lanka, Maharagama National Youth Service Council, 2009, National Survey on Needs of Youth in Sri Lanka, 2008/09, Maharagama.

Perera,G., 2007, “Voice of Youth - Empowering the future in Sri Lanka” Viewed on line: http://www.dailymirror.lk/2007/04/03/ft/03.asp

-The Ministry of Defence bears no responsibility for the ideas and views expressed by the contributors to the Opinion section of this web site-